|

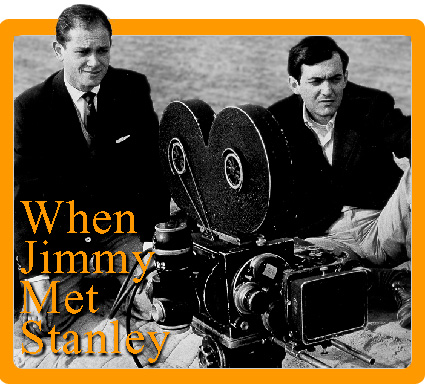

Meet Harris and Kubrick, two can-do guys growing up

babyface smart in New York.

It's 1955. Jimmy is looking for his break licensing

films to broadcasters when Stanley, an aquaintance through

a mutual pal, inquires if there is a chance to place

his 68-minute first feature "Fear And Desire"

somewhere on the glowing box. No dice. It turned out

the rights are hopelessly tied up in an estate dispute.

"We were like the characters in 'Marty,'"

says Harris. "What are you gonna do? I don't know.

What are you gonna do?"

Jimmy

screens Stanley's home-made second feature "Killer's

Kiss." He's impressed. Here is a guy who knows

what he's doing with a film camera. Likewise, Stanley

senses that James B. Harris has the goods to play ball

in the game of film finance and production. Jimmy proposes

a partnership, Stanley agrees and Harris-Kubrick is

born. Jimmy

screens Stanley's home-made second feature "Killer's

Kiss." He's impressed. Here is a guy who knows

what he's doing with a film camera. Likewise, Stanley

senses that James B. Harris has the goods to play ball

in the game of film finance and production. Jimmy proposes

a partnership, Stanley agrees and Harris-Kubrick is

born.

Now Harris realizes with some alarm that he better

get some hot property onboard for his partner to direct.

He makes a beeline to the mystery section at Scribner's

on 5th Avenue and pulls a book off the shelf. By some

serendipity it's ideal. Stanley listens to the pitch

and says, "Absolutely."

Clean Break by Lionel White is a hard-knock

pulp that uses a nested structure to unlock the edgy

game of a racetrack heist  gone

bad. To reduce a lot of work into one sentence, the

two New Yorkers went to Hollywood and made a hell of

a good movie — a domino effect of action, suspense,

comedy and tragedy. It was called "The Killing"

(1956). Shot in 24 days for $330,000, it featured a

firecracker cast of noir vets like Sterling Hayden and

Marie Windsor. Thanks to Stanley's visual know-how and

a Gatling gun script belt-loaded by pulp writer Jim

Thompson, "The Killing" joins ranks with "Kiss

Me Deadly" and "Touch of Evil" as the

requiem for classic noir cinema. The title hit the Top

10 list with Time's yearly critic, a major coup —

but as the B-feature behind a Robert Mitchum actioner

called "Bandido," it was basically undistinguished

in its initial run. gone

bad. To reduce a lot of work into one sentence, the

two New Yorkers went to Hollywood and made a hell of

a good movie — a domino effect of action, suspense,

comedy and tragedy. It was called "The Killing"

(1956). Shot in 24 days for $330,000, it featured a

firecracker cast of noir vets like Sterling Hayden and

Marie Windsor. Thanks to Stanley's visual know-how and

a Gatling gun script belt-loaded by pulp writer Jim

Thompson, "The Killing" joins ranks with "Kiss

Me Deadly" and "Touch of Evil" as the

requiem for classic noir cinema. The title hit the Top

10 list with Time's yearly critic, a major coup —

but as the B-feature behind a Robert Mitchum actioner

called "Bandido," it was basically undistinguished

in its initial run.

The

partnership had found its rhythm, however, and Harris-Kubrick

hit the bull's-eye with their follow-up. "Paths

Of Glory" was adapted from a novel Stanley remembered

from age 14. Where "The Killing" was effective

genre stuff, this was the war picture par excellence,

thematically ambitious, technically superb, affectingly

played, showcasing Kirk Douglas at the height of his

screen powers, a palpable hit with critics and exhibitors

alike. It had violence, it had Kirk, it had tragic pathos.

It made people cry. The

partnership had found its rhythm, however, and Harris-Kubrick

hit the bull's-eye with their follow-up. "Paths

Of Glory" was adapted from a novel Stanley remembered

from age 14. Where "The Killing" was effective

genre stuff, this was the war picture par excellence,

thematically ambitious, technically superb, affectingly

played, showcasing Kirk Douglas at the height of his

screen powers, a palpable hit with critics and exhibitors

alike. It had violence, it had Kirk, it had tragic pathos.

It made people cry.

Harris-Kubrick was on the map and on a creative roll.

Jimmy had their next project in his sites. It was the

talk of the city's literary scene — a notorious,

possibly immoral, not-yet published new novel by someone

named Nabakov.

Harris was intrigued. Then Stanley's friend and co-scripter

on "Paths Of Glory," Calder Willingham,  piped

up he knew about Nabakov from Cornell University and

he had heard about this. The trio wanted to read this

novel damn fast. It arrived in the post from Putnam's

and the three friends split the manuscript of Lolita

into thirds and relayed their way through the novel. piped

up he knew about Nabakov from Cornell University and

he had heard about this. The trio wanted to read this

novel damn fast. It arrived in the post from Putnam's

and the three friends split the manuscript of Lolita

into thirds and relayed their way through the novel.

"We loved it," says Jimmy. "I said,

'my God, we have got to do this. I don't know how we

are going to get it made but we have got to do this.'"

Lolita was the ideal change of key for Harris-Kubrick,

from crime and war to a bizarre love story; a subversive

tragedy leavened with wit; and a dangerous liaison with

roots in DeSade and Restoration English drama and branches

in Kubrick's later titles "Barry Lyndon" and

"Eyes Wide Shut."

Right at the start Jimmy and Stanley agreed on their

approach. The public  knew

the book was controversial. They would expect a dirty

old man, a deviant, someone to despise. Instead, in

"Lolita" they would find a man destroyed by

unrequited love – by fate, folly, vanity. Whether

you called it a perversion or a fatal flaw, he was someone

you could actually feel for. Stanley delivered the dramatic

goods with the kind of genius for which he was quickly

becoming famous. knew

the book was controversial. They would expect a dirty

old man, a deviant, someone to despise. Instead, in

"Lolita" they would find a man destroyed by

unrequited love – by fate, folly, vanity. Whether

you called it a perversion or a fatal flaw, he was someone

you could actually feel for. Stanley delivered the dramatic

goods with the kind of genius for which he was quickly

becoming famous.

Meanwhile it was Jimmy's job navigating the rocky straits

between nay-saying agents, fickle financiers, The Legion

of Decency, the MPAA censor, and scores of critics who

demanded perfect fidelity to the novel (at the time

the auteur theory favored the novelist). It took

years to get the cameras rolling. There were lengthy

delays (Harris labored on setting up "Lolita"

while Stanley shot "Spartacus" for Kirk Douglas).

Lead actors fell in and out. Studio deals collapsed.

But

Harris kept up the fight to make a new, better, more

challenging picture with "Lolita." He ran

the risk of the public hating it because they hated

the subject and critics hating it because they loved

the novel. Instead the title turned a profit and critics

recognize it as vital, the black comedy, or comic tragedy,

that preceded "Dr. Strangelove." But

Harris kept up the fight to make a new, better, more

challenging picture with "Lolita." He ran

the risk of the public hating it because they hated

the subject and critics hating it because they loved

the novel. Instead the title turned a profit and critics

recognize it as vital, the black comedy, or comic tragedy,

that preceded "Dr. Strangelove."

It's a tribute to Jimmy it exists.

|

Jimmy

screens Stanley's home-made second feature "Killer's

Kiss." He's impressed. Here is a guy who knows

what he's doing with a film camera. Likewise, Stanley

senses that James B. Harris has the goods to play ball

in the game of film finance and production. Jimmy proposes

a partnership, Stanley agrees and Harris-Kubrick is

born.

Jimmy

screens Stanley's home-made second feature "Killer's

Kiss." He's impressed. Here is a guy who knows

what he's doing with a film camera. Likewise, Stanley

senses that James B. Harris has the goods to play ball

in the game of film finance and production. Jimmy proposes

a partnership, Stanley agrees and Harris-Kubrick is

born. gone

bad. To reduce a lot of work into one sentence, the

two New Yorkers went to Hollywood and made a hell of

a good movie — a domino effect of action, suspense,

comedy and tragedy. It was called "The Killing"

(1956). Shot in 24 days for $330,000, it featured a

firecracker cast of noir vets like Sterling Hayden and

Marie Windsor. Thanks to Stanley's visual know-how and

a Gatling gun script belt-loaded by pulp writer Jim

Thompson, "The Killing" joins ranks with "Kiss

Me Deadly" and "Touch of Evil" as the

requiem for classic noir cinema. The title hit the Top

10 list with Time's yearly critic, a major coup —

but as the B-feature behind a Robert Mitchum actioner

called "Bandido," it was basically undistinguished

in its initial run.

gone

bad. To reduce a lot of work into one sentence, the

two New Yorkers went to Hollywood and made a hell of

a good movie — a domino effect of action, suspense,

comedy and tragedy. It was called "The Killing"

(1956). Shot in 24 days for $330,000, it featured a

firecracker cast of noir vets like Sterling Hayden and

Marie Windsor. Thanks to Stanley's visual know-how and

a Gatling gun script belt-loaded by pulp writer Jim

Thompson, "The Killing" joins ranks with "Kiss

Me Deadly" and "Touch of Evil" as the

requiem for classic noir cinema. The title hit the Top

10 list with Time's yearly critic, a major coup —

but as the B-feature behind a Robert Mitchum actioner

called "Bandido," it was basically undistinguished

in its initial run.  The

partnership had found its rhythm, however, and Harris-Kubrick

hit the bull's-eye with their follow-up. "Paths

Of Glory" was adapted from a novel Stanley remembered

from age 14. Where "The Killing" was effective

genre stuff, this was the war picture par excellence,

thematically ambitious, technically superb, affectingly

played, showcasing Kirk Douglas at the height of his

screen powers, a palpable hit with critics and exhibitors

alike. It had violence, it had Kirk, it had tragic pathos.

It made people cry.

The

partnership had found its rhythm, however, and Harris-Kubrick

hit the bull's-eye with their follow-up. "Paths

Of Glory" was adapted from a novel Stanley remembered

from age 14. Where "The Killing" was effective

genre stuff, this was the war picture par excellence,

thematically ambitious, technically superb, affectingly

played, showcasing Kirk Douglas at the height of his

screen powers, a palpable hit with critics and exhibitors

alike. It had violence, it had Kirk, it had tragic pathos.

It made people cry. piped

up he knew about Nabakov from Cornell University and

he had heard about this. The trio wanted to read this

novel damn fast. It arrived in the post from Putnam's

and the three friends split the manuscript of Lolita

into thirds and relayed their way through the novel.

piped

up he knew about Nabakov from Cornell University and

he had heard about this. The trio wanted to read this

novel damn fast. It arrived in the post from Putnam's

and the three friends split the manuscript of Lolita

into thirds and relayed their way through the novel.

knew

the book was controversial. They would expect a dirty

old man, a deviant, someone to despise. Instead, in

"Lolita" they would find a man destroyed by

unrequited love – by fate, folly, vanity. Whether

you called it a perversion or a fatal flaw, he was someone

you could actually feel for. Stanley delivered the dramatic

goods with the kind of genius for which he was quickly

becoming famous.

knew

the book was controversial. They would expect a dirty

old man, a deviant, someone to despise. Instead, in

"Lolita" they would find a man destroyed by

unrequited love – by fate, folly, vanity. Whether

you called it a perversion or a fatal flaw, he was someone

you could actually feel for. Stanley delivered the dramatic

goods with the kind of genius for which he was quickly

becoming famous. But

Harris kept up the fight to make a new, better, more

challenging picture with "Lolita." He ran

the risk of the public hating it because they hated

the subject and critics hating it because they loved

the novel. Instead the title turned a profit and critics

recognize it as vital, the black comedy, or comic tragedy,

that preceded "Dr. Strangelove."

But

Harris kept up the fight to make a new, better, more

challenging picture with "Lolita." He ran

the risk of the public hating it because they hated

the subject and critics hating it because they loved

the novel. Instead the title turned a profit and critics

recognize it as vital, the black comedy, or comic tragedy,

that preceded "Dr. Strangelove."