|

Kenny: At the end of my five

years at Def Jam I get an offer from MCA to come head up their

Black Music Division creative department in New York. At the

time it was a big opportunity. Even Cey and Steve were like,

you should take it. It's big money, big opportunity. You should

roll with it.

I

met Deanna at Def Jam. That's the big part I'm missing. She

grew up in New York City, went to an all-girl prep school

called Marymount and then to UMass. She always wanted to do

advertising. She went to Oxford for a year and then interned

at an ad agency in Manhattan. She also landed jobs with a

music producer and then a director's rep, meanwhile waitressing

all around town. Deanna was working I

met Deanna at Def Jam. That's the big part I'm missing. She

grew up in New York City, went to an all-girl prep school

called Marymount and then to UMass. She always wanted to do

advertising. She went to Oxford for a year and then interned

at an ad agency in Manhattan. She also landed jobs with a

music producer and then a director's rep, meanwhile waitressing

all around town. Deanna was working

at RCA Promotions when she left for Russell Simmons and Def

Jam.

We met the day of her interview. And as soon as we met, we

totally hit it off. We tried to keep it a bit secret, but

as you know in the office, everyone ends up knowing about

it. I tried to be a mack about it. It was groovy. It was great

her being there but it was better when she left. Too

many people in your mix. All the girls there knew how much

I was into her. We got married in August of 1995, and had

Bianka in 1999 and baby boy Noah in 2002.

MCA was a great experience because it was more of a business

experience for me. Just dealing with corporate

America at the time. MCA was a whole different ball of wax

to me because it was just corporate America to the hilt. Run

by Hank Shocklee, part of the Bomb Squad from Public Enemy,

and David Harleston, who used to be the president of Def Jam.

That's how I got the job. MCA's creative services

department was in L.A. I didn't want to move to L.A. They

said, why don't you stay in New York and set up a studio.

I hired this cat named Drew Fitzgerald to help me get that

stuff off the ground. Basically they set up a department for

us to work out of New York and I'd have to go back and forth

to L.A. as much as needed.

Then after the mergers, Seagram's, and all that mess happened,

it kind of left us in a weird spot.

Five-O: When MCA first brought

you on, what kind of projects were you working on?

Kenny: That was 1995. I worked on Al Green, Chanté

Moore, and a bunch of new bands, stuff for Uptown. New Edition.

As far as my worst complete nightmare project, New Edition

pretty much hits it (laughs). You know what MCA taught me

a lot, was handling  these

big projects, these projects that mean a lot to people, and

not that at Def Jam they didn't, but it was so close, tight

knit. Almost everybody took responsibility. That was the kind

of family environment at Def Jam. MCA didn't have that at all.

It was definitely corporate

America. You were on your own. It was like, dude, handle your

business, or we're pointing fingers. I learned how to handle

myself in those type situations. It was a completely different

experience, just as valuable as Def Jam. these

big projects, these projects that mean a lot to people, and

not that at Def Jam they didn't, but it was so close, tight

knit. Almost everybody took responsibility. That was the kind

of family environment at Def Jam. MCA didn't have that at all.

It was definitely corporate

America. You were on your own. It was like, dude, handle your

business, or we're pointing fingers. I learned how to handle

myself in those type situations. It was a completely different

experience, just as valuable as Def Jam.

Basically Jay Boberg came in a president of MCA Records,

lured me from the Big Apple, gave me a promotion and all this

stuff. Deanna and I said, we'll try it out for a

couple years. We were here for a year when we started really

getting into living here in L.A. I had to go back to New York

a lot, but you know, New York seemed more grimy, more dirty,

more hectic, more hustling, and I just liked the fact that

here is just more chill.

When I got here I was working on Rahsaan Patterson. Then

came the big merger where Mary J. Blige came to MCA, and Uptown

folded out. The Mary J. Blige Share My World album

came up and I did that and started to make my niche in L.A.

MCA were good to me. Made it smooth. Work was flowing well.

The next big transition for me was after a wave of lay-offs.

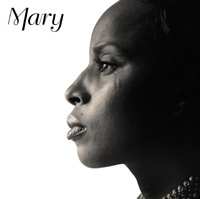

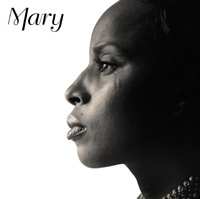

It was around the time of the Mary album, I used Albert

Watson for the shoot. At the time Deanna was pregnant. We

got married in '95. I felt a wave of

uncertainty at MCA and I didn't like the feeling. Things were

no longer safe there.

Because the company had changed mottos, Black Music Division

was folded into MCA by Jay and no longer separate, I felt

very strongly I should not be doing just black music. I should

get to do other types of  music.

They gave me the band The Murmurs to do. It was fun, a cool

job. But that was it. After that I didn't hear anything. I

remember a meeting where one of the excuses was, it's about

who connects with the artist more. That seemed convenient

and I had huge issues with that and I didn't see it really

changing too much. I realized that wherever you start is more

so how people see you. If you start as an intern, even when

you go up the ranks, depending on how the structure is, a

lot of the time people will still have that intern philosophy

about you. Until you move to another place, and they've never

known you as an intern. I felt a little of that as a "black

music designer." music.

They gave me the band The Murmurs to do. It was fun, a cool

job. But that was it. After that I didn't hear anything. I

remember a meeting where one of the excuses was, it's about

who connects with the artist more. That seemed convenient

and I had huge issues with that and I didn't see it really

changing too much. I realized that wherever you start is more

so how people see you. If you start as an intern, even when

you go up the ranks, depending on how the structure is, a

lot of the time people will still have that intern philosophy

about you. Until you move to another place, and they've never

known you as an intern. I felt a little of that as a "black

music designer."

The goal was, we need to diversify. I needed to make a way

to do that. Then when we were pregnant, we became aware, you

know, we want to make out own schedule. Things are changing

in the industry. We were like, maybe it's time to make a move,

and go independent. It's taking a chance

because you have a family, but it was let's just do

it. We feel confident enough to get the work.

Once we made the decision to leave, I'd just finished Mary.

I told them I'd be there through the end of the year. I did

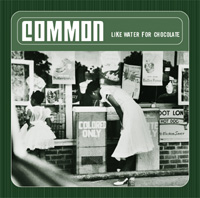

the Common project, Like Water For Chocolate. But it

kind of crept up on them. They were like, huh?

Leaving, it's been awesome. It's been much more work, though,

than I anticipated. I do admit. I didn't have the company

mentality, even though it's a small company. I had the freelance

mentality. You know, see a movie during the day. Occasionally

we still do that, but it's just a little

harder now. What happened was, we got so much work right at

the beginning, we were forced to bring people on to help us.

We showed our stuff around and everybody started calling.

Dreamworks, Arista, MCA was still using us, different labels,

different projects, Forefront Christian label in Nashville.

Not

all black, all rock bands and stuff it's so refreshing

to work on different stuff. We're still known for our urban

music, but we're up for everything. Now we're doing Third

Eye Blind. We did Babyface and Usher and Blu Cantrell for Arista. We did Ashanti

for Def Jam. Not

all black, all rock bands and stuff it's so refreshing

to work on different stuff. We're still known for our urban

music, but we're up for everything. Now we're doing Third

Eye Blind. We did Babyface and Usher and Blu Cantrell for Arista. We did Ashanti

for Def Jam.

Having a company, you deal with all sorts of issues versus

working for a company. It's hard work. But this year for us

has been a year of transition. We have to move into a new

studio. It's huge for all of us right now. We want a boutique

studio, four or five people max. Super quality work. That's

what we want to be known for. Not right for everybody kind

of scenario. Diversifying. Getting out of just doing music.

It goes back to my college days, getting people to think.

To me, it's all about what the idea is. It's not

necessarily that it's an album cover or poster. What's the

idea behind it? That's what makes it special, creative.

That's what we started to concentrate on, to get people to

see us for being idea people. That's why we don't call

ourselves just a design firm. We call ourselves visual communicators.

It broadens us a little more than, OK, they design album covers.

Last year we started to diversify. And this year we've made

a big push to infiltrate the movie side of it. The reason

I did that is the same reason I went to Chris Austopchuck's

office in New York: because I like music. It was getting back

to the idea: what do we like? What are we into?

The movie side is a difficult issue to get into. There's

definitely a clique  of

companies that everyone uses.

Thankfully, God's looking out for us and we've been able to

work with one of the big studios, Fox, on this summer movie

by Roland Emmerich called "Tomorrow." We did ideas

for Artisan for "Standing in the Shadows of Motown."

Poster stuff, which was great. of

companies that everyone uses.

Thankfully, God's looking out for us and we've been able to

work with one of the big studios, Fox, on this summer movie

by Roland Emmerich called "Tomorrow." We did ideas

for Artisan for "Standing in the Shadows of Motown."

Poster stuff, which was great.

My old boss, Steve Carr, is a director now. He did "Doctor

Dolittle 2" and he's directing this new Eddie Murphy

called "Daddy Daycare." So hopefully we can work

a little with him on some projects. Also an old friend of

ours named Brett Ratner is also a director. He just finished

"Red Dragon." We're trying to hook up with our old

buddies (laughs).

Five-O: What about directing

a movie yourself?

Kenny: I'd like to. But I

wouldn't see myself as a career director, like that's the

be-all and end-all scenario. For me, there's certain stories

I would like to tell, to write

and direct, but I don't think I would be on the director's

train per se, like, OK send me scripts, let's see what's out

there to direct. I think it would be something more personal.

It's a case of, this is another outlet to do something.

We're also talking about starting a magazine possibly. Different

things that we're leading up to, but Gravillis Inc. is the

conduit for everything. And we're trying to have fun with

it. My philosophy is, it's pointless working your behind off

especially for someone with kids when we're

working, we need to enjoy it as much as possible. And I think

you're better at work when you realize it.

The reason I think we have so much success with projects

like The Roots and Common is strictly based on

relationships. In reference to creating something that speaks

for the band, speaks artistically for you, you have to have

a relationship with the band it's trust. Trust is a

huge part of it.

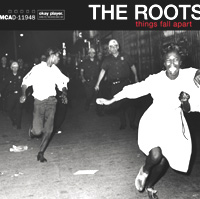

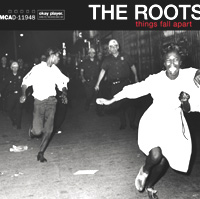

If we go back to things fall apart (The Roots' 1999

album masterpiece), I went to New York, met with the band,

and art-wise they were completely off in another direction.

They had some bad illustration ready for the cover. It was

like, all the guys in the group at the bottom of  the

sea with chains on. It was, it was terrible (laughs).

It was just bad. And I spoke to ?uestlove, Amir Thompson,

I was like, Amir, this is horrible. I really like you guys'

stuff a lot, and I'm here because I really want everyone to

see how great this record's going to be and I really want

the imagery to match. You guys worked this hard. Think about

it, the cover, it's face of your music. You spend a year,

or however long, making some music, and at the end you have

this cover, you want it to be the best it can be, surely. the

sea with chains on. It was, it was terrible (laughs).

It was just bad. And I spoke to ?uestlove, Amir Thompson,

I was like, Amir, this is horrible. I really like you guys'

stuff a lot, and I'm here because I really want everyone to

see how great this record's going to be and I really want

the imagery to match. You guys worked this hard. Think about

it, the cover, it's face of your music. You spend a year,

or however long, making some music, and at the end you have

this cover, you want it to be the best it can be, surely.

The Roots, with them guys, I was able to build a relationship

of trust. After things fall apart, the imagery

of things falling apart in society proved so successful, the

guys decided to go ahead and trust me. And it shows, because

on their next album, The Roots Come Alive, the live thing,

we put just the mic on the cover, by itself in a concert hall.

I remember one time Tariq, Black Thought telling Tim Reid

II, The Roots' marketing man at MCA, "just let Kenny

come up with something and we'll do it." That's

very unusual. You don't hear that. People do not say that

usually. And that shows the level of trust. I'm always showing

them what I'm doing, always get their approval, but there's

a sense of freedom in work, and I feel complete liberty to

take the approach I'm working on. I think that's so important.

It hardly ever happens. I think most designers will tell you:

if out of the year you do 20 packages, you can probably count

on one hand the packages where you have complete freedom.

Five-O: And to have that when

the music is reaching new highs

Kenny: Yeah, it's really special.

A lot of the time when you get artists that are true artists,

they have a respect for art. What ends up happening is they

have a respect for

your opinion, as an artist to another  artist.

When that happens is when sparks fly and really great things

happen. You have two forces working together as one creative

entity. And one's not banging its head against the other,

even if there are disagreements. They're resolved in a

creative way. artist.

When that happens is when sparks fly and really great things

happen. You have two forces working together as one creative

entity. And one's not banging its head against the other,

even if there are disagreements. They're resolved in a

creative way.

Five-O: things fall apart,

The Roots album, was named after the 1958 novel by Nigerian

writer Chinua Achebe, who drew his title from the famous Yeats

poem "The Second Coming." That's a hell of a pedigree.

So how did you decide, I'm going to take a documentary, war

correspondent-approach to this package?

Kenny: For me, the title was

so social, you know? It felt like it needed to be dealt with

in a realistic way. That's where the idea came from for the

documentary photos. They were social events. People still

talk about seeing the woman running from the police

that ended up being the main cover. It was like, look at that

the fear on that woman's face as she's running. The

dead hand with the ace in the fingers. Black churches burnt

down South. Little kid left orphaned by war. We did like 20

different images. Some were so intense it was like, there's

no way we can use these.

Amir is very much into his artwork. A lot of people are,

but the level of what that means is variable. For him it means

a lot. He wants to be recognized for his artwork by people

who recognize artwork. It's not about wanting his boys to

like it, moms, dads, uncles, brothers, to think he

looks cool. The album cover shows your level of intelligence

as an artist.

Five-O: Especially contrasted

to the jewelry, car and booty obsessions being sold as the

ultimate

Kenny: Totally opposite of

the bling bling and all that stuff. I think the success of

it is great, because it shows people's willingness to think.

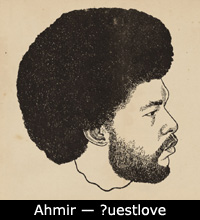

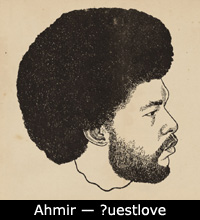

The

new one, Phrenology was a little different, because

it had a title that meant something. That was The Roots saying

to us, "Phrenology" is the album title: go. Literally.

We were like, "O...K!" So it was time to study phrenology,

and it was fun in the sense we took the time to find out what

phrenology was all about, where it came from, and that all

helped. The

new one, Phrenology was a little different, because

it had a title that meant something. That was The Roots saying

to us, "Phrenology" is the album title: go. Literally.

We were like, "O...K!" So it was time to study phrenology,

and it was fun in the sense we took the time to find out what

phrenology was all about, where it came from, and that all

helped.

(Phrenology is a cousin of palm-reading, a pseudo-science

based on "reading" the shape of the skull and features.

Sometimes was used to advocate racist fantasies about

higher and lower "types".)

The great thing about the cover is when you match it up to

all the definitions and terms, it's a great connection for

bringing it all up to do, a total Roots scenario, compartments

of the mind. You get to know the personality of the band,

it's just much easier. We went ahead and did. We sent it to

them. They were like, amazing. A couple little tweaks and

we were done. Projects like that? I love.

Plus I think The Roots have come with a record that is not

what people expect and is not in the box people have put them

in. That's the best kind of artist. "Do not dare put

us in a box or we will smash it," you know what I mean?

We try to do that with the artwork, too. Make people think,

make them do a double-take.

Five-O: They're one of the

only groups in hip hop to really surprise you.

Kenny: I really agree with

that. That's why I feel honored to do their stuff. Because

creatively it's a treasure chest for us to be involved.

Five-O: Another of your artists

is also at the forefront: Common.

Kenny: Definitely. Common

is an amazingly nice guy, the nicest guy in hip hop that I

know. Rashid, that's his name. The cool thing about him is

he's always trying to go the next mile, to the next level.

And he's so open to creative ideas. With him the  process

is like, "Kenny, let's just try to push it, let's be

creative, let's try to be on the level of the music."

This is someone for whom his album cover means a lot. We went

through like three different campaigns before we came up with

the final for Electric Circus. This was the best one,

the one that made the most sense. One was a woman, an icon

with a '70s kind of feel. We ended up going with the idea

of what it took for him to make this record. His thoughts,

ideas, it worked on a personal level for him. The circus being

the people that influenced him to make the record. That hit

the nail on the head for him a Sgt. Pepper kind of

vibe. process

is like, "Kenny, let's just try to push it, let's be

creative, let's try to be on the level of the music."

This is someone for whom his album cover means a lot. We went

through like three different campaigns before we came up with

the final for Electric Circus. This was the best one,

the one that made the most sense. One was a woman, an icon

with a '70s kind of feel. We ended up going with the idea

of what it took for him to make this record. His thoughts,

ideas, it worked on a personal level for him. The circus being

the people that influenced him to make the record. That hit

the nail on the head for him a Sgt. Pepper kind of

vibe.

With this one for Common, same thing: I think people are

going to be thrown off in a good way. Again, it's that

smashing out of the box. I prefer to do that, and people hate

it or they love it. Rather than I give you something you expect

and you like it OK. For me as an artist, that means more.

I think that's what art's about. Number one, it's all relative.

And it's about expression. I can express

something exactly how I want it. How you receive it is how

you receive it. Both The Roots and Common do that to most

of their ability.

Five-O: How about Common's

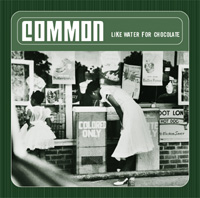

breakthrough album Like Water For Chocolate?

Kenny: Common brought that

image to us. For us it was about designing it in a timeless,

throwback way. Back to that Alabama time. We got a little

girl I knew as the model. It was  amazing

because she had the perfect face, a black child back in the

'40s. Rashid really led us on that one and we took the ball

and ran with it. One thing we did, we put the track titles

on the spine of the CD case. Other people might have been

like, why are you doing that? No one does that. Rashid loved

it. He was like, I've never seen that. That's why we have

success and fun on these jobs. It goes back to personal relationship.

I mean, Rashid must have called here twice every day during

this last project. It's cool. amazing

because she had the perfect face, a black child back in the

'40s. Rashid really led us on that one and we took the ball

and ran with it. One thing we did, we put the track titles

on the spine of the CD case. Other people might have been

like, why are you doing that? No one does that. Rashid loved

it. He was like, I've never seen that. That's why we have

success and fun on these jobs. It goes back to personal relationship.

I mean, Rashid must have called here twice every day during

this last project. It's cool.

Five-O: It's a different game

from Roots and Common with some of the commercial projects.

Kenny: With some of the other

acts it's a little more corporate: make me look good. I gotta

look good, great,

amazing. And that's fine too. But being a good designer means

bringing out the best in the environment you're in. So when

you're in the "make me look good" environment, you

do your best. Also don't be upset if it's not the award-winning

art piece. It's not that  type

of thing. In college, your mindset is everything has to be

the award-winning art piece. In the real world, once you start

understanding different projects require different mindsets,

then you'll be more successful. Once I understand this person

needs to look good they're not going to be into having

their face half-cropped off, because that's not what they're

into. It might be cool to you, but that's not what the artist

needs. It's an apple-sauce box, versus Common or The Roots,

where you cut off half their face and it doesn't come close

to doing what you need to do to throw these guys off, you

know. type

of thing. In college, your mindset is everything has to be

the award-winning art piece. In the real world, once you start

understanding different projects require different mindsets,

then you'll be more successful. Once I understand this person

needs to look good they're not going to be into having

their face half-cropped off, because that's not what they're

into. It might be cool to you, but that's not what the artist

needs. It's an apple-sauce box, versus Common or The Roots,

where you cut off half their face and it doesn't come close

to doing what you need to do to throw these guys off, you

know.

|

|

Five-O: I saw Kenny gave you

a full credit on the Phrenology and Electric Circus

packages. That's a pretty

good step for a guy who's still fresh to L.A. a couple years

out of school. Did you have an artistic background as

a kid?

Matt Taylor: I was an artistic

kid, pretty much encouraged by mom and dad to do my stuff.

In high school I got into photography. When I got to  college

I thought that was going to be my major. I took a graphic

design class and it clicked. When I was a kid growing up near

Chicago, I paid attention to billboards and ads I later realized

were "graphic design." You know, why do some letters

have little feet, seraphs, and some don't? I took a class

and it all sort of made sense and I kind of forgot about photography

and focused in on design. college

I thought that was going to be my major. I took a graphic

design class and it clicked. When I was a kid growing up near

Chicago, I paid attention to billboards and ads I later realized

were "graphic design." You know, why do some letters

have little feet, seraphs, and some don't? I took a class

and it all sort of made sense and I kind of forgot about photography

and focused in on design.

I got my bachelor of arts in graphic design from University

of Missouri. My junior and senior year I was president of

the design club and we got some funding to bring a speaker.

One of my instructors, Jean, knew this guy in L.A. named Tim

Stedman, who worked at a record company. So we got him to

come out and speak. (Tim Stedman, VP at MCA Records, handles

album art for acts including blink-182, New Found

Glory, Lyle Lovett and Res.) So he came and he liked my work.

About a month before I graduated in '99, he called me up and

asked me to come interview as soon as I graduated.

Five-O: Nice segue.

Matt: I didn't even have my

book fully together. Came out did the interview and a couple

weeks later got the job as a design assistant at MCA.  I

helped on all sorts of projects I guess my one thing

was the Dice Raw package (never released), I helped Tim on

the Mint Royale package, then all the assistant things, all

the ads, full on designing merch stuff, which was cool. I

helped on all sorts of projects I guess my one thing

was the Dice Raw package (never released), I helped Tim on

the Mint Royale package, then all the assistant things, all

the ads, full on designing merch stuff, which was cool.

But the thing that was really neat about Kenny, he saw that

given more opportunity I could do more. So once he brought

me on to Gravillis Inc. in 2001, I slowly did more and more.

And he was really excited about the amount of effort I put

into it. Actually Tom Huck, the illustrator on The Roots Phrenology,

is a guy from my  school.

When we started the project Kenny was talking about how it

should look, and I was like, oh wow, I know this guy who would

be perfect. So it was really truly a collaborative thing.

Kenny was definitely art-directing this thing, but I was able

to art direct Tom and deal with him. school.

When we started the project Kenny was talking about how it

should look, and I was like, oh wow, I know this guy who would

be perfect. So it was really truly a collaborative thing.

Kenny was definitely art-directing this thing, but I was able

to art direct Tom and deal with him.

Five-O: Obviously it was the

right move to make, from support at MCA to busting it out

over here.

Matt: It worked perfectly.

I needed that amount of time I spent at MCA to grow from college

to real world designer. Then Gravillis called and said we

want someone to work with

us, it's getting heavy. It's timing, you know. Once I saw

how things were working here, Kenny kind of gave me more and

more. I did some smaller CDs like The Sounds of Blackness

greatest hits anthology. It would be like, here's this project,

handle it. There was a Christian R&B group, Out Of Eden,

that I handled. It was really good experience.

Five-O: And you're also branching

out to movies. How's that been?

Matt: It's a trip. I'm very

blessed to do this stuff with Kenny. He's known as the music

guy, but he wanted us both to jump in on the same level on

the movie side and them to associate us both with this new

aspect of the company.

Five-O: The stuff I've seen

you're working on for the summer movie "Tomorrow" is

of a piece with what you do on the music side: its' a concept.

Is that going to be accepted?

Matt: That's what Gravillis

Inc. is all about. We want to take it way out left and have

you bring us back. So we do the heavy conceptual stuff that's

smarter.

And it was appreciated on the "Tomorrow" campaign.

That's another

reason I think I work so well here... it's our approach to

design. It has to be a strong idea before anything else. If

you look at 80%, 90%, 99% of the movie stuff, it's formulaic.

We're not saying we're going to change the world, but we're

going to try to freshen up the cocktail. smarter.

And it was appreciated on the "Tomorrow" campaign.

That's another

reason I think I work so well here... it's our approach to

design. It has to be a strong idea before anything else. If

you look at 80%, 90%, 99% of the movie stuff, it's formulaic.

We're not saying we're going to change the world, but we're

going to try to freshen up the cocktail.

Five-O: Kenny's got his eye

on maybe someday telling stories as a movie-maker. What about

you, do you have any

ambitions you're holding out for a later day?

Matt: For him to do that,

he needs somebody to run the show here, so on the short end,

I'd be excited to run the Gravillis Inc. scene. As far as

myself, I'm crazy about what I do. I'm lucky because I love

music and I love

design. If I can be as established as Kenny is in the music

business, that's definitely a goal for me.

Five-O: What were you listening

to when you were younger?

Matt: I would have Barry Manilow

on the little Mickey Mouse turntable and then KISS Destroyer

would come on after Manilow Live. I knew there was so much

out there and I always wanted to know more. It wasn't just

one thing that I liked. I like rock, I like techno, I like

hip hop. Once you

understand the genre it's a part of a huge palette. It's the

same as my approach to design, music, movies, whatever, once

you understand what that particular piece is about, the conventions,

you can approach it in the best possible way.

Five-O: What's your family

background?

Matt: My dad is a retired pilot.

My mom is a housewife who's done some jobs. My brother's in

school for airline training he worked for a long time

in Utah as a camp

counselor. I'm sort of the black  sheep.

For a while there, Pops didn't figure out what his son was

all about. Then it was, OK, he's creative. They fostered that.

My dad's dad did little editorial cartoons. He always encouraged

me to keep trying. sheep.

For a while there, Pops didn't figure out what his son was

all about. Then it was, OK, he's creative. They fostered that.

My dad's dad did little editorial cartoons. He always encouraged

me to keep trying.

L.A.'s the perfect place in time for me right now. I can

see building up my work and what I do and maybe taking

somewhere else. I love Colorado and envision myself living

there someday, maybe with my own studio. Dealing with all

these folks in New York, there's no reason I couldn't be in

Peoria, Illinois doing the same thing.

Five-O: How do your friends

back home react to what you're doing?

Matt: I remember about ten

years ago when I was a teen-age kid listening to music trying

to figure it all out, I go see this guy named Jeff "Cool

Breeze" Gordon, who works at Streetside Records in Columbia,

Missouri. I go, I'm sick of Eazy E and NWA I need something

more intelligent.

Jeff goes, hold on. And as fate would have it he comes back

with two CDs: Common Resurrection and The Roots Do You Want

More?!

So this last Thanksgiving when I was home, I went over to

the store and showed Cool Breeze the new Common and Roots

packages. It was pretty cool. I wanted to show him that Missouri

was holding it down.

|

I

met Deanna at Def Jam. That's the big part I'm missing. She

grew up in New York City, went to an all-girl prep school

called Marymount and then to UMass. She always wanted to do

advertising. She went to Oxford for a year and then interned

at an ad agency in Manhattan. She also landed jobs with a

music producer and then a director's rep, meanwhile waitressing

all around town. Deanna was working

I

met Deanna at Def Jam. That's the big part I'm missing. She

grew up in New York City, went to an all-girl prep school

called Marymount and then to UMass. She always wanted to do

advertising. She went to Oxford for a year and then interned

at an ad agency in Manhattan. She also landed jobs with a

music producer and then a director's rep, meanwhile waitressing

all around town. Deanna was working  these

big projects, these projects that mean a lot to people, and

not that at Def Jam they didn't, but it was so close, tight

knit. Almost everybody took responsibility. That was the kind

of family environment at Def Jam. MCA didn't have that at all.

It was definitely corporate

America. You were on your own. It was like, dude, handle your

business, or we're pointing fingers. I learned how to handle

myself in those type situations. It was a completely different

experience, just as valuable as Def Jam.

these

big projects, these projects that mean a lot to people, and

not that at Def Jam they didn't, but it was so close, tight

knit. Almost everybody took responsibility. That was the kind

of family environment at Def Jam. MCA didn't have that at all.

It was definitely corporate

America. You were on your own. It was like, dude, handle your

business, or we're pointing fingers. I learned how to handle

myself in those type situations. It was a completely different

experience, just as valuable as Def Jam.  music.

They gave me the band The Murmurs to do. It was fun, a cool

job. But that was it. After that I didn't hear anything. I

remember a meeting where one of the excuses was, it's about

who connects with the artist more. That seemed convenient

and I had huge issues with that and I didn't see it really

changing too much. I realized that wherever you start is more

so how people see you. If you start as an intern, even when

you go up the ranks, depending on how the structure is, a

lot of the time people will still have that intern philosophy

about you. Until you move to another place, and they've never

known you as an intern. I felt a little of that as a "black

music designer."

music.

They gave me the band The Murmurs to do. It was fun, a cool

job. But that was it. After that I didn't hear anything. I

remember a meeting where one of the excuses was, it's about

who connects with the artist more. That seemed convenient

and I had huge issues with that and I didn't see it really

changing too much. I realized that wherever you start is more

so how people see you. If you start as an intern, even when

you go up the ranks, depending on how the structure is, a

lot of the time people will still have that intern philosophy

about you. Until you move to another place, and they've never

known you as an intern. I felt a little of that as a "black

music designer." Not

all black, all rock bands and stuff it's so refreshing

to work on different stuff. We're still known for our urban

music, but we're up for everything. Now we're doing Third

Eye Blind. We did Babyface and Usher and Blu Cantrell for Arista. We did Ashanti

for Def Jam.

Not

all black, all rock bands and stuff it's so refreshing

to work on different stuff. We're still known for our urban

music, but we're up for everything. Now we're doing Third

Eye Blind. We did Babyface and Usher and Blu Cantrell for Arista. We did Ashanti

for Def Jam. of

companies that everyone uses.

Thankfully, God's looking out for us and we've been able to

work with one of the big studios, Fox, on this summer movie

by Roland Emmerich called "Tomorrow." We did ideas

for Artisan for "Standing in the Shadows of Motown."

Poster stuff, which was great.

of

companies that everyone uses.

Thankfully, God's looking out for us and we've been able to

work with one of the big studios, Fox, on this summer movie

by Roland Emmerich called "Tomorrow." We did ideas

for Artisan for "Standing in the Shadows of Motown."

Poster stuff, which was great.  the

sea with chains on. It was, it was terrible (laughs).

It was just bad. And I spoke to ?uestlove, Amir Thompson,

I was like, Amir, this is horrible. I really like you guys'

stuff a lot, and I'm here because I really want everyone to

see how great this record's going to be and I really want

the imagery to match. You guys worked this hard. Think about

it, the cover, it's face of your music. You spend a year,

or however long, making some music, and at the end you have

this cover, you want it to be the best it can be, surely.

the

sea with chains on. It was, it was terrible (laughs).

It was just bad. And I spoke to ?uestlove, Amir Thompson,

I was like, Amir, this is horrible. I really like you guys'

stuff a lot, and I'm here because I really want everyone to

see how great this record's going to be and I really want

the imagery to match. You guys worked this hard. Think about

it, the cover, it's face of your music. You spend a year,

or however long, making some music, and at the end you have

this cover, you want it to be the best it can be, surely.

artist.

When that happens is when sparks fly and really great things

happen. You have two forces working together as one creative

entity. And one's not banging its head against the other,

even if there are disagreements. They're resolved in a

creative way.

artist.

When that happens is when sparks fly and really great things

happen. You have two forces working together as one creative

entity. And one's not banging its head against the other,

even if there are disagreements. They're resolved in a

creative way.  The

new one, Phrenology was a little different, because

it had a title that meant something. That was The Roots saying

to us, "Phrenology" is the album title: go. Literally.

We were like, "O...K!" So it was time to study phrenology,

and it was fun in the sense we took the time to find out what

phrenology was all about, where it came from, and that all

helped.

The

new one, Phrenology was a little different, because

it had a title that meant something. That was The Roots saying

to us, "Phrenology" is the album title: go. Literally.

We were like, "O...K!" So it was time to study phrenology,

and it was fun in the sense we took the time to find out what

phrenology was all about, where it came from, and that all

helped.  process

is like, "Kenny, let's just try to push it, let's be

creative, let's try to be on the level of the music."

This is someone for whom his album cover means a lot. We went

through like three different campaigns before we came up with

the final for Electric Circus. This was the best one,

the one that made the most sense. One was a woman, an icon

with a '70s kind of feel. We ended up going with the idea

of what it took for him to make this record. His thoughts,

ideas, it worked on a personal level for him. The circus being

the people that influenced him to make the record. That hit

the nail on the head for him a Sgt. Pepper kind of

vibe.

process

is like, "Kenny, let's just try to push it, let's be

creative, let's try to be on the level of the music."

This is someone for whom his album cover means a lot. We went

through like three different campaigns before we came up with

the final for Electric Circus. This was the best one,

the one that made the most sense. One was a woman, an icon

with a '70s kind of feel. We ended up going with the idea

of what it took for him to make this record. His thoughts,

ideas, it worked on a personal level for him. The circus being

the people that influenced him to make the record. That hit

the nail on the head for him a Sgt. Pepper kind of

vibe.  amazing

because she had the perfect face, a black child back in the

'40s. Rashid really led us on that one and we took the ball

and ran with it. One thing we did, we put the track titles

on the spine of the CD case. Other people might have been

like, why are you doing that? No one does that. Rashid loved

it. He was like, I've never seen that. That's why we have

success and fun on these jobs. It goes back to personal relationship.

I mean, Rashid must have called here twice every day during

this last project. It's cool.

amazing

because she had the perfect face, a black child back in the

'40s. Rashid really led us on that one and we took the ball

and ran with it. One thing we did, we put the track titles

on the spine of the CD case. Other people might have been

like, why are you doing that? No one does that. Rashid loved

it. He was like, I've never seen that. That's why we have

success and fun on these jobs. It goes back to personal relationship.

I mean, Rashid must have called here twice every day during

this last project. It's cool.  type

of thing. In college, your mindset is everything has to be

the award-winning art piece. In the real world, once you start

understanding different projects require different mindsets,

then you'll be more successful. Once I understand this person

needs to look good they're not going to be into having

their face half-cropped off, because that's not what they're

into. It might be cool to you, but that's not what the artist

needs. It's an apple-sauce box, versus Common or The Roots,

where you cut off half their face and it doesn't come close

to doing what you need to do to throw these guys off, you

know.

type

of thing. In college, your mindset is everything has to be

the award-winning art piece. In the real world, once you start

understanding different projects require different mindsets,

then you'll be more successful. Once I understand this person

needs to look good they're not going to be into having

their face half-cropped off, because that's not what they're

into. It might be cool to you, but that's not what the artist

needs. It's an apple-sauce box, versus Common or The Roots,

where you cut off half their face and it doesn't come close

to doing what you need to do to throw these guys off, you

know. college

I thought that was going to be my major. I took a graphic

design class and it clicked. When I was a kid growing up near

Chicago, I paid attention to billboards and ads I later realized

were "graphic design." You know, why do some letters

have little feet, seraphs, and some don't? I took a class

and it all sort of made sense and I kind of forgot about photography

and focused in on design.

college

I thought that was going to be my major. I took a graphic

design class and it clicked. When I was a kid growing up near

Chicago, I paid attention to billboards and ads I later realized

were "graphic design." You know, why do some letters

have little feet, seraphs, and some don't? I took a class

and it all sort of made sense and I kind of forgot about photography

and focused in on design. I

helped on all sorts of projects I guess my one thing

was the Dice Raw package (never released), I helped Tim on

the Mint Royale package, then all the assistant things, all

the ads, full on designing merch stuff, which was cool.

I

helped on all sorts of projects I guess my one thing

was the Dice Raw package (never released), I helped Tim on

the Mint Royale package, then all the assistant things, all

the ads, full on designing merch stuff, which was cool. school.

When we started the project Kenny was talking about how it

should look, and I was like, oh wow, I know this guy who would

be perfect. So it was really truly a collaborative thing.

Kenny was definitely art-directing this thing, but I was able

to art direct Tom and deal with him.

school.

When we started the project Kenny was talking about how it

should look, and I was like, oh wow, I know this guy who would

be perfect. So it was really truly a collaborative thing.

Kenny was definitely art-directing this thing, but I was able

to art direct Tom and deal with him.  smarter.

And it was appreciated on the "Tomorrow" campaign.

That's another

reason I think I work so well here... it's our approach to

design. It has to be a strong idea before anything else. If

you look at 80%, 90%, 99% of the movie stuff, it's formulaic.

We're not saying we're going to change the world, but we're

going to try to freshen up the cocktail.

smarter.

And it was appreciated on the "Tomorrow" campaign.

That's another

reason I think I work so well here... it's our approach to

design. It has to be a strong idea before anything else. If

you look at 80%, 90%, 99% of the movie stuff, it's formulaic.

We're not saying we're going to change the world, but we're

going to try to freshen up the cocktail. sheep.

For a while there, Pops didn't figure out what his son was

all about. Then it was, OK, he's creative. They fostered that.

My dad's dad did little editorial cartoons. He always encouraged

me to keep trying.

sheep.

For a while there, Pops didn't figure out what his son was

all about. Then it was, OK, he's creative. They fostered that.

My dad's dad did little editorial cartoons. He always encouraged

me to keep trying.